The “Visible Hand” Part 4: China’s Cryptocurrency Marks a New Frontier

Dave Gallagher, CFA

In July, we introduced our commentary series focused on how Chinese government policies shape investment opportunities in China, in emerging markets and globally. Beijing’s “visible hand” contrasts with the “invisible hand” shaping free markets—and provides a guidepost for identifying areas of the market that offer greater growth potential and those that are vulnerable to increased risk.

Digital currencies are the focus of our fourth case study on how the visible hand of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) creates significant disruption and opportunity. We’ll discuss both the ongoing cryptocurrency crackdown and the plans to launch the first central bank digital currency (CBDC).

China’s Crypto Crackdown

China has been cracking down on cryptocurrencies for years, but the enforcement has been inconsistent. As a result, investors have found workarounds and the market has flourished. However, there is a growing consensus that the CCP means business now, and this time will be different.

The last big crackdown occurred in 2017 when regulators simultaneously banned domestic cryptocurrency exchanges and initial coin offerings. These bans were intended to make it more difficult for the average citizen to participate in the crypto market, but most active Chinese traders eventually found ways to access foreign exchanges and remained a considerable force in the global crypto market. The failure to address legal gray areas combined with the availability of cheap energy (crypto mining is electricity intensive) also fostered an explosion in domestic mining operations—at the peak it is estimated that China accounted for approximately 75% of the world’s bitcoin mining capacity.

The current crackdown was initiated in mid-May shortly after cryptocurrencies started selling off on news that Tesla had suspended the acceptance of bitcoin because of environmental concerns. The first shot across the bow was a statement by the Chinese central bank (the Peoples Bank of China, or PBoC) reiterating that financial institutions and payment companies were prohibited from providing any services related to cryptocurrencies. A joint statement from three financial industry associations echoing the same warning quickly followed. Later that same week, the Financial Stability and Development Committee (FSDC) of the State Council (China’s cabinet) issued a national-level directive to crack down on both the mining and trading of cryptocurrencies as part of a campaign to control financial risks.

The growing consensus that this time is different arguably has more to do with the source than the actual directives. The FSDC is a particularly noteworthy source because it is led by Vice Premier Liu He, President Xi Jinping’s right-hand man on the economy. Now that top leadership is championing the crypto crackdown, it is sure to be a priority. We are already seeing signs of increased execution: key provincial governments have banned cryptocurrency mining, regulators have summoned bank leadership teams to reiterate the ban on providing cryptocurrency services, companies have shut down amid allegations of providing crypto trading and services, the microblogging site Weibo suspended crypto-related accounts, and there have been mass arrests of people suspected of using cryptocurrencies to launder money. Top crypto mines also quickly announced plans to leave China, and by July, it was estimated that nearly half of the world’s bitcoin miners had gone dark.

How does China’s Digital Yuan Work?

China’s Tang and Song dynasties invented paper money more than a thousand years ago. Now, the Chinese are arguably on the cusp of leading the next major innovation in the global monetary system by turning legal tender into computer code.

We highlighted the CCP’s ambition to launch the first central bank digital currency (CBDC) in a post last summer (see “Central Banks’ Digital Currency Aspirations Provide Tailwinds to Current Leaders in the Global Payments Ecosystem”). The formal name of China’s sovereign digital currency is the DCEP (Digital Currency Electronic Payment), but it is more commonly referred to as the e-CNY or digital yuan. The DCEP project started in 2014, but really gained momentum in mid-2019 after Facebook announced it was backing the launch of a new cryptocurrency called Libra (see “Perspectives on Libra, Facebook’s Proposed Cryptocurrency”). (Libra was recently rebranded in anticipation of its 2021 launch and is now called Diem.) Most major governments saw Libra as a threat to monetary sovereignty. The Chinese government’s concerns were even more pronounced because the Libra Association did not include any Chinese companies, and the basket of reserves backing the Libra did not include any yuan-denominated assets.

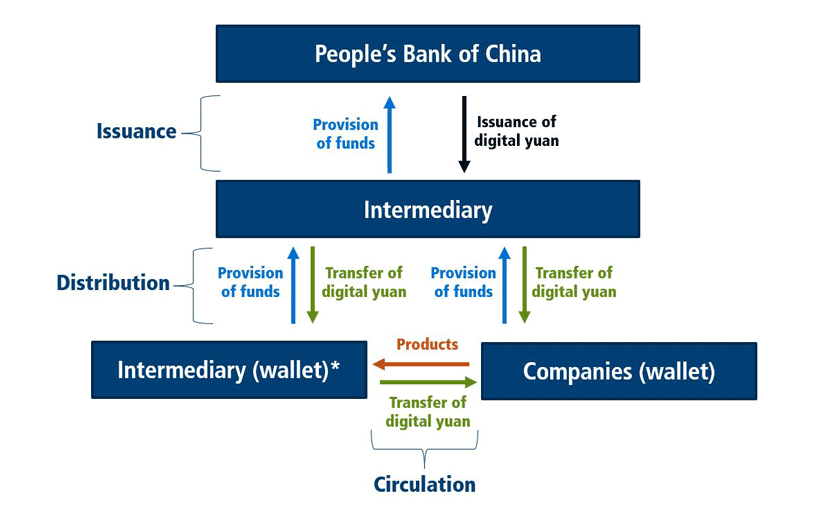

DCEP is the digital form of China’s fiat money (the digital yuan) and is a substitute or replacement for paper money (M0). Technical details are limited, but unlike most other cryptocurrencies, DCEP is run on a centralized closed network that provides the PBoC with complete access and control. Similar to paper money, the digital yuan does not require internet access or pay interest. The issuance and distribution is via a two-tiered system where PBoC issues the digital yuan to intermediaries (first tier), and then it is distributed to retail market participants via digital wallets (second tier). The intermediaries currently include the major state-owned banks and large payment companies like Alibaba, Tencent and UnionPay. The two-tiered system combined with the lack of interest payments is expected to minimize any potential competition with bank demand (M1) and time deposits (M2) due to concerns that disintermediating the banks would risk destabilizing the broader financial system. To ensure nationwide acceptance, the government has already mandated that all merchants who accept digital payments must accept the digital yuan.

*Digital yuan may also be used between individuals and between companies. Source: Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry, “China Aiming to Issue a Central Bank Digital Currency—Expected Macro-Level Effects,” Chi Hung Kwan, compiled by Chi Hung Kwan based on a speech made by Mu Changchun, at the Third China Finance 40 Forum on August 10, 2019.

Although there is currently no timetable for the official nationwide launch of the DCEP, the government seeks to achieve extensive domestic circulation by the 2022 Winter Olympics. The initial pilot program was launched in the spring of 2020 across four cities: Shenzhen, Suzhou, Chengdu, and Xiong’an. Over the past year, the pilot program has been extended to several more cities, many local and international companies have participated in the testing, select government employees have been paid in digital yuan, and more than ¥200 million in digital yuan have been distributed to local residents via lotteries. Although the PBoC has largely focused on retail use by the public, the central bank has started working with the Hong Kong Monetary Authority to test the use of DCEP for cross-border payments. The PBoC also recently announced that it will explore cross-border payment programs in coordination with other central banks.

China’s Cryptocurrency Policies Align with the CCP’s Strategic Goals

There are many motivations behind the CCP’s ongoing crypto crackdown and development of the first CBDC, which are all consistent with the core objective of defending and consolidating power through the promotion of social stability via continued economic growth, improved living standards, and increased control.

Economic Growth

- Financial stability. The government sees cryptocurrencies and the duopoly in mobile payments as potential sources of financial instability. Cryptocurrencies are an obvious threat because they undermine financial regulation, and the concentration of trillions in mobile payments increases the risk of hacks and other technological failures.

- Capital allocation. Mining for cryptocurrencies is diverting technological resources away from more productive end markets. Meanwhile, a digital currency would lower the cost of maintaining physical cash supplies, which is estimated at approximately 0.5% of GDP.

- Monetary policy. The digital yuan should provide the central bank with a more real-time view and a better understanding of what’s happening in the economy as well as the ability to improve transmission through more tailored policies. For instance, the central bank could use digital yuan to distribute economic stimulus with specific parameters for the timing and types of purchases. The elimination of paper money would also arguably facilitate the implementation of a negative rate policy at some point in the future.

- Yuan internationalization. The internationalization of the yuan is a long-term goal for China and has been included in several five-year plans. While macroeconomic constraints and legal considerations represent formidable impediments to the global use of the yuan, the digital yuan arguably provides the CCP with a new avenue for promoting the use of China’s currency in cross-border transactions. If China maintains its lead in CBDC technology and standards, it can help other countries build their own digital currencies and develop a network of interoperable digital currencies.

Living Standards

- Financial inclusion. China already has the highest digital payment penetration in the world, but a large segment of the population still transacts exclusively in cash because they lack bank accounts or live in rural areas without reliable internet access. The digital yuan solves both these issues because it does not require a bank account and people can complete transactions without an internet connection.

- Asset bubbles. Cryptocurrencies have been prone to speculative bubbles. If it grew big enough, a bubble could cause widespread hardship when it popped. The implosion of this sort of bubble would be more likely to spark social unrest in a place like China where the government is seen as playing a bigger role in individual wealth creation.

- Environment. As standards of living improve in China, the government has increased its focus on reducing pollution. Bitcoin mining in China had been expected to generate more than 130 million metric tons of carbon emissions by 2024, more than the annual carbon emissions of some countries.1

- Lower costs. The DCEP wallets will charge no transaction fees (interchange, network, or merchant) and thus would provide a huge savings to small and medium-sized businesses.

Control

- Data. Over the years, the CCP has become increasingly dependent on big technology firms for data, but the digital yuan threatens to flip the script by providing Chinese authorities with even more granular transaction and savings data. And, if the relationship becomes more contentious, it’s not inconceivable that the government could completely disintermediate third-party electronic payment and wallet providers at some point in the future.

- Illegal activity. Cash and decentralized cryptocurrencies provide the anonymity needed to fund criminal activity, which is clearly not consistent with an authoritarian society built on law and order. Eliminating decentralized cryptocurrencies and introducing a completely traceable digital yuan that could phase out cash over time would make criminal activity much more difficult to fund.

- Closed capital account. It’s widely known that Chinese nationals use cash and cryptocurrency to circumvent the $50,000 per year foreign exchange limit. The elimination of decentralized cryptocurrencies and the complete digitalization of cash would greatly reduce this practice.

Investment Implications

There are many unknowns regarding how China’s crypto crackdown and race to launch the first CBDC will play out. But disruption on this scale is likely to create big opportunities for some companies and significant headwinds for others. We expect the digitalization of money to drive continued growth in digital payments. However, digitization also lowers the barriers to entry for new players and thus could foster increased competition in global digital payments as well as more broadly across the financial tech industry.

The impact of China’s digital currency will be felt across industries beyond fintech. The adoption of the digital yuan will generate vast amounts of data, creating increased demand for AI and other technology needed to store and analyze this data. Our portfolios include many technology companies that we believe will benefit from big data and the increased production of data globally. Data needs to be stored, which increases demand for companies at the cutting edge of cloud technology and hardware. And, the data also needs to be analyzed, providing tailwinds for AI, database and software companies.

Conversely, local and global industries that have historically assisted in or benefited from Chinese nationals’ efforts to circumvent capital controls would face headwinds in an environment where anonymous wealth transfers (in cash and cryptocurrencies) are increasingly replaced by a digital currency where the central bank is able to trace every movement.

1 For example, the 2016 carbon emissions of Czech Republic and Qatar were lower according to a Nature Commissions study, “Policy assessments for the carbon emission flows and sustainability of Bitcoin blockchain operation in China,” April 6, 2021.

Opinions, estimates, forecasts, and statements of financial market trends that are based on current market conditions constitute our judgment and are subject to change without notice. The views and strategies described may not be appropriate for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations.

As a result of political or economic instability in foreign countries, there can be special risks associated with investing in foreign securities, including fluctuations in currency exchange rates, increased price volatility and difficulty obtaining information. In addition, emerging markets may present additional risk due to potential for greater economic and political instability in less developed countries.

This material is distributed for informational purposes only. The information contained herein is based on internal research derived from various sources and does not purport to be statements of all material facts relating to the information mentioned and, while not guaranteed as to the accuracy or completeness, has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable.

18905 0821

Archived material may contain dated performance, risk and other information. Current performance may be lower or higher than the performance quoted in the archived material. For the most recent month-end performance information, please CLICK HERE. Archived material may contain dated opinions and estimates based on our judgment and are subject to change without notice, as are statements of financial market trends, which are based on current market conditions at the time of publishing. We believed the information provided here was reliable, but do not warrant its accuracy or completeness. This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. This material has been prepared for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for, accounting, legal or tax advice. References to future returns are not promises or even estimates of actual returns a client portfolio may achieve. Any forecasts contained herein are for illustrative purposes only and are not to be relied upon as advice or interpreted as a recommendation.

Performance data quoted represents past performance, which is no guarantee of future results. Current performance may be lower or higher than the performance quoted. The principal value and return of an investment will fluctuate so that your shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Performance reflected at NAV does not include the Fund’s maximum front-end sales load. Had it been included, the Fund’s return would have been lower. For the most recent month-end fund performance information visit www.calamos.com.

Archived material may contain dated performance, risk and other information. Current performance may be lower or higher than the performance quoted in the archived material. For the most recent month-end fund performance information visit www.calamos.com. Archived material may contain dated opinions and estimates based on our judgment and are subject to change without notice, as are statements of financial market trends, which are based on current market conditions at the time of publishing. We believed the information provided here was reliable, but do not warrant its accuracy or completeness. This material is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument. The views and strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. This material has been prepared for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide, and should not be relied on for, accounting, legal or tax advice. References to future returns are not promises or even estimates of actual returns a client portfolio may achieve. Any forecasts contained herein are for illustrative purposes only and are not to be relied upon as advice or interpreted as a recommendation.

Performance data quoted represents past performance, which is no guarantee of future results. Current performance may be lower or higher than the performance quoted. The principal value and return of an investment will fluctuate so that your shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than their original cost. Performance reflected at NAV does not include the Fund’s maximum front-end sales load. Had it been included, the Fund’s return would have been lower.

Archived on November 22, 2021Cookies

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies. Learn more about our cookie usage.