Investment Team Voices Home Page

Investment Team Voices Home Page

The “Visible Hand” Part 2: How Beijing’s Education Policy Is Reshaping Investment Opportunity

Nick Niziolek, CFA

Our previous post introduced our series of commentary focused on how Chinese government policies shape investment opportunities in China, the emerging markets and globally. Beijing’s “visible hand” contrasts with the “invisible hand” shaping free markets—and provides a guidepost for identifying areas of the market offering greater growth potential versus those that are vulnerable to increased risk.

Our first case study about how the visible hand of China’s Communist Party (CCP) creates significant disruption and opportunity focuses on the education sector. In January, the CCP increased regulation of the Chinese education sector, specifically targeting the after-school-tutoring (AST) market. The AST market is highly fragmented, but three publicly listed companies have achieved great success in expanding their product offerings and gaining market share, achieving a peak combined market capitalization of over $100 billion. In recent months, we have seen this valuation shrink to $30 billion as new details unfold about additional proposed regulations and their impact on these business models.

January 27, 2021- June 28, 2021

| Total Return | |

|---|---|

| GSX Techedu | -89.52% |

| New Oriental Education and Technology Group | -52.18% |

| TAL Education Group | -68.74% |

| MSCI Emerging Market Index | 1.56% |

Source: Bloomberg. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

While we do not have exposure to this industry, our team has stayed abreast of the near-daily news flow, separating the signal from the noise. We have been thinking through the larger implications these policies may have on adjacent industries and broader policy creation. As understood today, these new regulations will eliminate the summer programs these private AST companies provide, with the government creating a free public option to minimize the disruption to working parents. The government is also increasing its free public tutoring options in the fall, which has the potential to significantly reduce the demand for private AST services.

As investors, we begin by asking why the CCP targeted this industry with increased regulation. The AST industry has realized tremendous growth in recent years, which has been driven by the high priority Chinese parents have placed on education. (In an extreme example, a group of high school students in China were hooked up to IV drips—in classrooms—to help them maintain peak performance as they prepped for exams.)

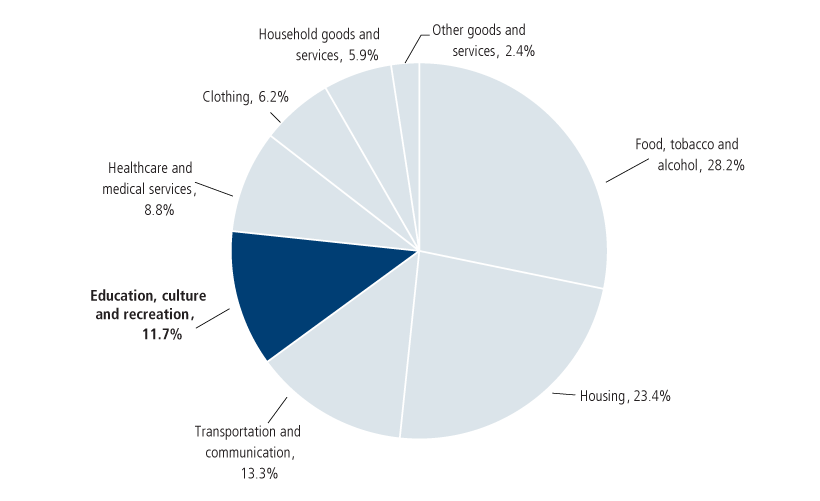

So, on the surface, the after-school tutoring market is an industry that appears aligned with the CCP’s objectives for full employment and increased purchasing power, as a well-educated workforce can aid China in moving up the value chain. However, private tutoring is an expensive undertaking (Figure 2), with families spending as much as 25% of their monthly consumption on education.

Households' Income and Consumption Expenditure in 2019

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

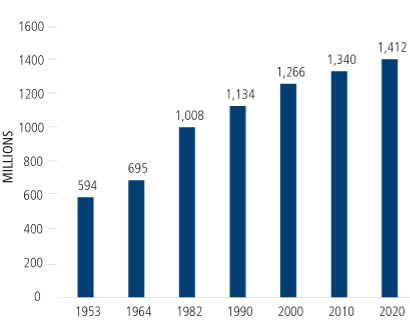

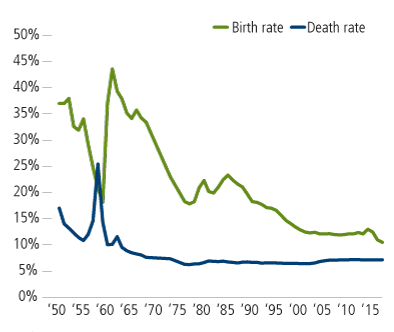

China has a well-publicized demographic issue, with its historical one-child policy resulting in a quickly aging population. Population growth is a key driver of economic growth, so a shrinking population is now proving detrimental to China’s primary objectives. In a bid to address this, the CCP has permitted two-child families and more recently three-child families. However, these moves have not resulted in a significant change in population growth, with many families choosing to have only one child.

Source: Bloomberg. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

One likely reason for this reluctance to have larger families is the cost of raising a child in China. As we noted, education is one of the larger cost components of childrearing in China, and the high cost of private tutoring also has created an inequality issue within China. With upper-class families able to allocate a larger percentage of their consumption budget to private tutoring, there is a perception that only the wealthy can continue to enter prestigious educational institutions in China. Through this lens, the private AST services that once may have been viewed as a benefit to Chinese society have now become a threat. The CCP has become focused on limiting the amount citizens can spend on these services while providing public alternatives, to not degrade the overall educational experience for their population.

Clearly, the publicly listed Chinese AST equities have seen a significant fundamental change in their business models, which is now being reflected in their stock prices. This brings us to our next question: What are the potential second- and third-derivative opportunities that may exist as a result of our understanding of the CCP’s increased focus on population growth?

First, we start by reviewing the basket of expenditures, where groceries and housing combined to account for nearly 50% of the average middle-class citizen’s consumption basket. This is why food inflation is a laser focus for the CCP and why affordable housing for the middle class has become an increasingly important policy prong. Also, we note that health care is becoming a larger percentage of the consumption basket, an area ripe for disruptive policy. In health care, we see more upside for companies that support the pharmaceutical industry via outsourced manufacturing and research trials as opposed to the drug developers who may see increased pricing pressure.

The CCP may be optimistic that by removing the education burden on its citizens, China will see more two- and three-child families formed, but we remain more skeptical. We will continue to monitor consumption patterns, as well as birth rate data to confirm or dispute our skepticism. Together, these changes would have a near-term impact on the diaper and dairy industries. As consumers spend less on education, we could see more money allocated for travel and consumer goods purchases, which would benefit our existing positioning in these industries and potentially provide a catalyst for increased exposure.

Conclusion

Utilizing policy as a framework to think through the changing landscape will provide us with key advantages in deploying capital, both to China and elsewhere. The CCP’s new stance on AST is just one very recent example of how policy can create significant disruption in an industry. Other examples—which we look forward to discussing in future posts—include China’s crackdown on crypto currency, the anti-monopoly campaign, and the releasing of commodity stockpiles. Similar to the changes in the AST market, these are all examples where new policies can have a direct impact on specific industries and companies, as well as second- and third-derivative risks and opportunities.

Opinions, estimates, forecasts, and statements of financial market trends that are based on current market conditions constitute our judgment and are subject to change without notice. The views and strategies described may not be appropriate for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations.

As a result of political or economic instability in foreign countries, there can be special risks associated with investing in foreign securities, including fluctuations in currency exchange rates, increased price volatility and difficulty obtaining information. In addition, emerging markets may present additional risk due to potential for greater economic and political instability in less developed countries.

This material is distributed for informational purposes only. The information contained herein is based on internal research derived from various sources and does not purport to be statements of all material facts relating to the information mentioned and, while not guaranteed as to the accuracy or completeness, has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable.

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index is considered generally representative of emerging market equities. Indexes are unmanaged, do not include fees or expenses and are not available for direct investment.

18898 0721O C

Cookies

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies. Learn more about our cookie usage.