Investment Team Voices Home Page

Investment Team Voices Home Page

Cyclical Themes: Outlook for the U.S. Dollar

Nick Niziolek, CFA and Dennis Cogan, CFA

Historically, the U.S. dollar’s strength or weakness has tended to be one of the most significant drivers in the relative performance of U.S. markets versus ex-U.S. developed markets and emerging markets. Also, the dollar tends to move relative to most major currencies in longer-term trends, typically five to 10 years with an overshoot on both the upside and downside. So, as U.S. domiciled global investors, understanding which dollar regime we are in matters greatly to being correctly positioned. We believe we are entering a new regime where the dollar will weaken against other global currencies.

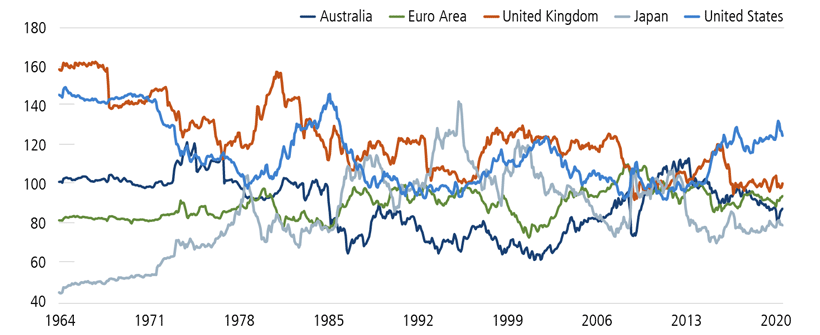

By most metrics, the U.S. dollar remains expensive relative to most major currencies. In most instances, it is near the upper end of historical valuation ranges. Valuation alone is not a catalyst, but it provides a framework to think through the potential magnitude of a move in these currencies. Given that during past regime shifts we’ve seen the dollar shift from an overvalued position to an undervalued position before the regime changes once again, we have considerable scope for depreciation when we do have that catalyst. We believe the pandemic has set into motion the conditions necessary to facilitate that change in regime.

Real Effective Exchange Rate Index

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Source: Macrobond.

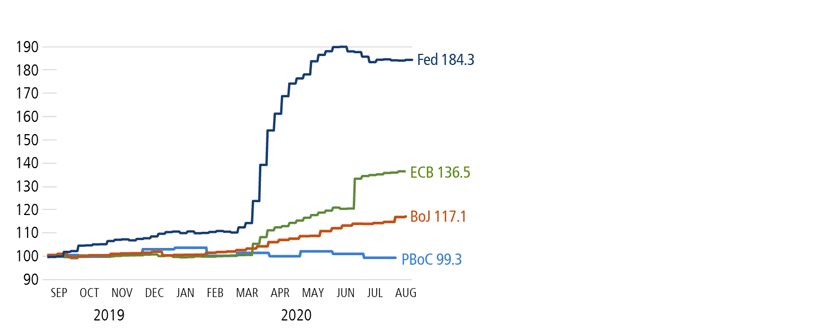

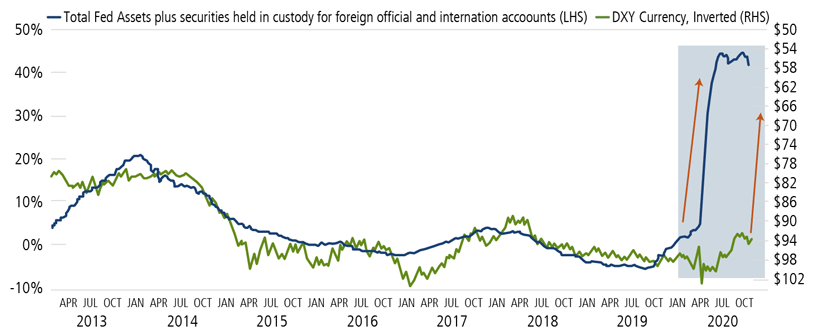

As the Covid crisis took hold, central banks around the world increased their balance sheets to provide liquidity. However, the Fed’s balance sheet grew much more rapidly than those of other central banks, as it sought to not make the same mistakes of its paced easing cycle heading into the GFC. Dollar swaps created during the GFC were quickly opened up and the world was awash with dollars, with the U.S. dollar peaking shortly thereafter as global liquidity conditions improved. Historical data shows a very tight correlation with the U.S. dollar and the size of the Fed’s balance sheet. As the supply of dollars increases, assuming constant demand, it intuitively makes sense that the value of the dollar would fall. History would show this to be the case, which provides a strong case for a weaker dollar outlook. Unless, of course the Fed were to begin another tightening cycle and reduce the size of its balance sheet. But at the recent Jackson Hole meetings, Chairman Powell made it very clear to the market that the Fed has no intentions of doing so in the near term. According to the Fed’s own forecasts, we may not see a tightening cycle begin again for at least a few years, with expectations that inflation will “run hot” before tightening is considered.

in Local Currency, Rebased at 100 in August 2019

Source: GaveKal Research, “The Past Is Another Country,” Louis-Vincent Gave, August 17, 2020. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Source: Macrobond. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. The U.S. Dollar Index (DXY) measures the value of the U.S. dollar relative to a basket of foreign currencies, including Euro Area, Canada, Japan, United Kingdom, Switzerland, Australia, and Sweden.

Now the skeptic in us says this may all be true, but are other countries going to stand by and let their currencies appreciate versus the U.S. dollar? For most of the past decade, this hasn’t been the case. Every time we had a bout of U.S. dollar strength, we saw the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan respond with their own easing measures to further weaken their currencies while the People’s Bank of China largely fixed the renminbi to the U.S. dollar with some movement. We believe the conditions have changed and there is now a greater willingness to allow the U.S. dollar to weaken. In a post-Brexit Europe, Germany is more concerned with keeping the European Union together than the impact of a stronger euro on its manufacturing sector. We believe the Covid-catalyzed $750 billion eurobond issue validates this view, as Germany has agreed to share the burden of this debt with its fellow eurozone members, something it was very much against post-GFC and pre-Brexit. In this new environment, with a focus more on internal reforms and rebuilding the strength of the eurozone, we believe the ECB will have a greater tolerance for euro strength.

Looking toward Asia, China’s President Xi is promoting a policy of “dual circulation” or internal consumption for China, reducing its dependence on exports and a weak currency. With the further opening of the equity and fixed income markets and relaxed restrictions on foreign direct investment, we’d expect the renminbi to continue to strengthen toward fair value and current leadership to permit this shift, in a departure from for the past decade. And while nothing as significant has changed in Japan, its increased reliance on Asia for trade should reduce the importance of the yen relative to the U.S. dollar as opposed to how the yen trades relative to other Asian currencies, so there should be some room to maneuver here as well.

Conclusion

We believe these factors all contribute to recent dollar weakness and signal a potential break in trend for the U.S. dollar. We are increasingly convinced that this is the beginning of a multi-year weakening cycle. While the Covid-induced declines in the dollar were sharp, we expect future depreciation to be more measured with periods of strength as well, but we do believe we are entering a new weak-dollar regime with significant implications for global risk assets.

Opinions, estimates, forecasts, and statements of financial market trends that are based on current market conditions constitute our judgment and are subject to change without notice. The views and strategies described may not be appropriate for all investors. References to specific securities, asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations.

As a result of political or economic instability in foreign countries, there can be special risks associated with investing in foreign securities, including fluctuations in currency exchange rates, increased price volatility and difficulty obtaining information. In addition, emerging markets may present additional risk due to the potential for greater economic and political instability.

18842 1020O C

Cookies

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies. Learn more about our cookie usage.